THE SCREENING ROOM

By Michael Coate

The date May 25, 1977 is immortalized forever as the “birthdate” of one

of the most popular movies ever made: “Star Wars.” Can you think

of any other movie whose release date is so well known?

In the 27 years since its release, “Star Wars” has gone from a modest

launch in a couple dozen theatres, to winning seven Academy Awards, to

selling hundreds of millions of

dollars of tie-in merchandise, to

influencing a generation of storytellers, and, according to Lucasfilm

Ltd. Vice President of Marketing Jim Ward, to selling over 100 million

home video units. The movie also positively influenced the

personal budget of George Lucas and

young stars like Harrison Ford, making them millionaires. Add to this, millions of DVDs recently welcomed

into many a home theatre library.

While audiences can now enjoy the movie on DVD, writer-director George

Lucas’ ongoing revisions have left a lot of fans feeling as though

there's a disturbance in the Force. Whether one approves or

disapproves of the changes made to the movie for the 1997 Special

Edition and the 2004 DVD version, what many do not realize is that

changes, no matter how subtle, have been made to “Star Wars” dating back

to its initial 1977 release. These include alternate sound mixes,

a revised opening scroll, and, possibly, some deleted scenes.

These adjustments, as well as the initial theatrical engagements, are

the subject of this article.

A Long Time Ago In A Theatre Far, Far Away....

For over two and a half decades, enthusiastic fans have related tales of

standing in long lines and recalling in astounding detail their first

impression of seeing the original movie in George Lucas’ legendary “Star

Wars” saga. Many moviegoers remember seeing the

movie on opening

day. Ah, but which opening day?The passage of time has caused

many people to forget that “Star Wars” (known today as “Star Wars:

Episode IV – A New Hope”) did not have the type of opening movies of

today enjoy: thousands of theatres simultaneously opening a film.

Rather, “Star Wars” opened initially in a mere 43 locations across the

United States.

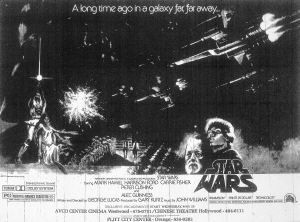

Southern California newspaper ad, May 15, 1977

Many sources over the years have cited 32 as the opening number of

engagements, and many trivia-minded fans may recognize the number.

The number 32 is correct... sort of. The film indeed opened with

32 engagements on the 25th of May, a mid-week Wednesday opening.

But what many may not realize is that additional bookings began on the

26th and 27th of May, which brought the opening weekend

engagement total

to 43. To say “Star Wars” opened in 32 theatres is literally

correct but does not tell the complete story.

The Original Engagements

So, who remembers the theatres in which “Star Wars” opened? For

the purpose of history and to provide a dose of trivia for the Jedi

Knights out there, what follows is the definitive list of original,

first-week engagements of “Star Wars.” (Fans may be interested in

knowing the list is more comprehensive than a similar listing posted on

the starwars.com website and the list provided to the press at the

junkets promoting the “Star Wars Trilogy” DVD release.)

Presentation Legend

* 70mm Dolby Stereo (magnetic)

** 35mm Dolby Stereo (optical)

*** 35mm mono (optical Dolby Stereo print)

Opened Wednesday, May 25, 1977:

ARIZONA

Phoenix: [Plitt] Ciné Capri ***

CALIFORNIA

Hollywood (Los Angeles): [Mann] Chinese *

Orange: [Plitt] City Center *

Sacramento: [Syufy] Century 25 ***

San Diego: [Mann] Valley Circle ***

San Francisco: [UA] Coronet *

San Jose: [Syufy] Century 22 ***

Westwood (Los Angeles): [GCC] Avco Center *

COLORADO

Denver: [Cooper Highland] Cooper **

DELAWARE

Claymont (Philadelphia, PA): [Sameric] Eric Twin Tri-State Mall ***

DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

Washington: [RKO/Stanley-Warner] Uptown **

ILLINOIS

Milan (Quad-City, IA/IL): [Redstone] Showcase **

INDIANA

Indianapolis: [Y&W] Eastwood **

KENTUCKY

Louisville: [Redstone] Showcase **

MASSACHUSETTS

Boston: [Sack] Charles **

MICHIGAN

Southfield (Detroit): [Nicholas George] Americana Complex **

MINNESOTA

Roseville (St. Paul): [Northwest] Roseville 4 **

St. Louis Park (Minneapolis): [GCC] St. Louis Park ***

NEW JERSEY

Edison (New York, NY): [GCC] Menlo Park ***

Lawrenceville (Philadelphia, PA): [Sameric] Eric Twin Lawrenceville ***

Paramus (New York, NY): [RKO/Stanley-Warner] Triplex Paramus *

Pennsauken (Philadelphia, PA): [Sameric] Eric Twin Pennsauken ***

NEW YORK

Hicksville (Long Island): [Mann] Twin South *

Manhattan (New York): [Loews] Astor Plaza *

Manhattan (New York) [Loews] Orpheum *

OHIO

Springdale (Cincinnati): [Redstone] Showcase **

OREGON

Beaverton (Portland): [Luxury] Westgate **

PENNSYLVANIA

Fairless Hills (Philadelphia): [Sameric] Eric Twin Fairless Hills ***

Monroeville (Pittsburgh): [Redstone] Showcase East **

Philadelphia: [Sameric] Eric's Place ***

UTAH

Salt Lake City: [Plitt] Centre ***

WASHINGTON

Seattle: [UA] Cinema 150 **

Opened Thursday, May 26, 1977:

KANSAS

Overland Park (Kansas City, MO): [Dickinson] Glenwood **

Opened Friday, May 27, 1977:

ILLINOIS

Calumet City (Chicago): [Plitt] River Oaks ***

Chicago: [Plitt] Esquire **

Lombard (Chicago): [GCC] Yorktown ***

Northbrook (Chicago): [Lubliner & Sterns] Edens **

IOWA

Des Moines: [Dubinsky] River Hills **

MISSOURI

Creve Coeur (St Louis): [Wehrenberg] Creve Coeur **

NEBRASKA

Omaha: [Douglas] Cinema Center **

OHIO

Dayton: [Chakeres] Dayton Mall **

TEXAS

Dallas: [GCC] Northpark I&II ***

Houston: [GCC] Galleria ***

An immediate sensation, “Star Wars” accumulated incredible per-screen

averages and broke numerous box office and attendance records at the few

locations lucky enough to have been playing the movie. The film

industry was in shock, and exhibitors everywhere couldn't wait to get

their hands on a print. The film’s distributor, 20th Century-Fox,

quickly added one extra engagement in each of the Los Angeles, New York,

and Cincinnati markets, as well as starting two engagements in Honolulu.

Fox had the lab cranking out prints as fast as they could as they

accelerated their plans for a broad, nationwide release.

The expanded release began with over 100 new engagements added

throughout the U.S. during the week beginning June 15, with additional

engagements added each week throughout the summer. At its peak in

August and September of 1977, “Star Wars” was playing in approximately

1,100 theatres in the United States and Canada, and was well on its way

to surpassing “Jaws” (1975) and becoming the new all-time box office

champ. In the fall of ’77, “Star Wars” began its engagements in

foreign countries under such titles as "Guerre Stellari," "Krieg Der

Sterne," and "La Guerra De Las Galaxias."

Why So Few Theatres?

Why was “Star Wars” released initially to so few theatres when, in

retrospect, the movie seemed like such a sure-fire hit?

“No one knew it was going to be a big hit,” remembers Ben Burtt, who was

responsible for Special Dialogue & Sound Effects on “Star Wars.”

“Nowadays, we take for granted that a big blockbuster will go out with

thousands of prints... and open in May. But back then the summer

special effects blockbuster did not exist.”

In the 1997 book “Empire Building: The Remarkable Real Life Story Of

Star Wars,” former Fox executive Gareth Wigan offered an explanation: “

‘Star Wars’ only opened in forty theaters because we could only get

forty theaters to book it. That's the astonishing thing.”

Although there were certainly fewer movie theatres in operation during

the 1970s compared with today, a wide release of a mainstream,

non-specialized film at that time typically meant a few hundred

engagements. To illustrate just how low the number of theatres was

in which “Star Wars” opened, even by 1977 standards, here is for

comparison a sample of some of the highly-anticipated films from the

spring and summer of 1977 followed by the opening-week number of

engagements.

The Spy Who Loved Me (200+)

Smokey And The Bandit (300+)

A Bridge Too Far (400+)

New York, New York (400+)

Rollercoaster (400+)

The Other Side Of Midnight (500+)

Exorcist II: The Heretic (700+)

Orca (700+)

The Deep (800+)

In “The Unauthorized Star Wars Compendium” (1999), Charles Lippincott,

former Lucasfilm Ltd. Vice President for Advertising, Publicity,

Promotion and Merchandising, mentioned that “If the film was redone

today, on the basis of the way movies are released with a couple of

thousand prints, it probably would have been unsuccessful.

Theaters didn't want the movie. We were lucky to get thirty

theaters to open it.” Lippincott also remarked on the importance

and prestige of getting booked in a major Hollywood theatre and the

difficulty Fox faced in finding such a venue for “Star Wars.” “At

that time, Hollywood Boulevard was still very important for opening

films. We only got on Hollywood Boulevard because the new Billy

Friedkin film [‘Sorcerer’] wasn't ready yet. It was supposed to be

ready by May 25 but wasn't, and we were given a month in the Chinese.

It was the only way we got into Grauman's.”

In contrast with the belief shared by many that “Star Wars” was a tough

sell to exhibitors, at least a few people at 20th Century-Fox had a

hunch the movie could be a hit if marketed carefully and given a

prestige-style platform release, specifically keeping the number of

engagements limited to key markets during the initial weeks of release.

(Films during 1977 given successful platform releases included “Julia,”

“The Turning Point,” and “Close Encounters Of The Third Kind.”)

Peter Myers, Vice President of Domestic Distribution for Fox at the

time, first saw “Star Wars” in a test screening three months before

scheduled release. He was very impressed, and contemplated the

best approach to marketing the film. “The answer,” Myers revealed

to the Associated Press shortly following the movie's opening, “was to

position the picture in the proper theaters and give it the proper

presentation so the people themselves could discover it and spread the

word.”

Being Blown Off The Screen

For the Hollywood exposé “Easy Riders, Raging Bulls: How The

Sex-Drugs-And-Rock 'N' Roll Generation Saved Hollywood” (1998), film

editor Bud Smith recalled his experience in seeing the coming

attractions trailer he had cut for “Sorcerer” in front of “Star Wars” at

the Chinese Theatre: “When our trailer faded to black, the curtains

closed and opened again, and they kept opening and opening, and you

started feeling this huge thing coming over your shoulder overwhelming

you, and heard this noise, and you went right off into space. It

made our film look like this little, amateurish piece of shit. I

told Billy [Friedkin], ‘We're fucking being blown off the screen.

You gotta go see this.’ ”

Mann's Chinese Theatre, 1977

To accommodate the opening of “Sorcerer” on June 24, 1977, the Hollywood

engagement of “Star Wars” was moved to another theatre a couple of

blocks down the street from the Chinese. Ultimately, the space

opera would have the last laugh. As “Sorcerer” failed to live up

to expectations while “Star Wars” continued to perform in stellar

fashion, Lucas’ epic moved back to the famous Chinese beginning August

3, where it stayed until June 1978. This marked the first time a

film had returned to the Chinese for a second first-run engagement in

the theatre's then fifty-year history. (The return of “Star Wars”

to the Chinese was highlighted by the foot and droid print ceremony in

the theatre's courtyard, an event thousands showed up to witness.)

Deleted Scenes – “I Saw That Scene!” “No, You Didn't.”

“Yes, I did!”

A controversy “Star Wars” has generated over the years is whether or not

any scenes were added to or deleted from the film after the initial

batch of prints were released to theatres. Many fans insist

changes were made, all of which Lucasfilm representatives have denied in

print and at many science-fiction and comic book conventions. Fan

recollections vary wildly and range from additional scenes featuring

Luke Skywalker and friend Biggs Darklighter, to an encounter with Jabba

the Hutt, to a brief bit with Chewbacca not scaring off the Death Star's

Mouse Robot, to a single shot of Luke throwing his grappling hook and

missing before throwing a second time successfully so he and Princess

Leia could swing across the Death Star chasm.

Deleted scene - Luke observing battle in space

While there is no doubt that the Jabba the Hutt scene and three scenes

set on Tatooine early in the movie featuring Luke (two of which included

Biggs) were deleted before the release, “The Unauthorized Star Wars

Compendium” includes a claim that the Luke-Biggs reunion scene in the

Rebel Hanger appeared in the original 1977 prints, only to be deleted

for the 1979 re-release, then re-instated for the 1997 Special Edition.

(The author of “The Unauthorized Star Wars Compendium” declined to be

interviewed for this article.)

Deleted scene - Luke reunited with Biggs

Memory can be a strange thing, and while it has been difficult to

confirm changes made to the film, an explanation for fans’ recollections

of seeing things can be traced to the movie's assortment of tie-in

publications and merchandise. For example, the Ballantine novel,

the Marvel comic book adaptation, the Topps bubblegum card series, the

documentary “The Making Of Star Wars,” and the books “The Star Wars

Storybook” and “The Art Of Star Wars” all featured text, photos,

footage, or cartoon renditions of scenes scripted and/or shot. Combined

with the lack of availability of a (legal) version of “Star Wars” on

home video formats until five years following the original theatrical

release, one can see how anyone with a vivid imagination can convince

themselves that they saw footage that may have never appeared in a

theatrical presentation of the movie.

Episode What?!

Despite the deleted scenes conflict, one thing is certain: the “Episode

IV: A New Hope” tag at the head of the opening scroll was not present in

the original prints of the film. The tag was seen for the first

time by audiences in America during the spring 1981 re-release, the

first re-release after the 1980 original release of the follow-up to

“Star Wars”: “The Empire Strikes Back.”

.jpg)

In a May 1980 interview with The Seattle Times, George Lucas explained

why “Star Wars” was originally released without an episode number or

subtitle: “I chickened out at the last minute thinking people aren't

going to understand what this is all about, so we dropped ‘Episode IV: A

New Hope.’ Now we're putting it back on. ‘Empire’ will be

called ‘Episode V.’ ”

.jpg)

The presence of an episode number and subtitle on the opening scroll of

“The Empire Strikes Back” caused some confusion and received coverage in

many film reviews and major news and film industry magazines, including

TIME, Newsweek, and American Cinematographer. Why the confusion?

Obviously, audiences had not yet seen a “Star Wars” movie begin with an

episode number or subtitle!

The “Empire” film review that appeared in The Washington Post clarified

the situation: “When ‘Star Wars’ is reissued, probably next summer, the

prints will include the subtitle, ‘Episode IV: A New Hope.’ This

adjustment may already be seen in the published screenplay, which came

out last winter in an attractive book called ‘The Art Of Star Wars.’ ”

Dolby Jumps To Hyperspace

The engrossing “Empire Of Dreams” documentary included on the “Star Wars

Trilogy” DVD bonus disc offers a portrait of George Lucas as a maverick,

independent filmmaker, and covers the production, release, and afterlife

of “Star Wars.” While the opening of the movie initially in only a

handful of theatres is represented, curiously, the documentary fails to

explore in detail the influence the film had on production and

exhibition technology, namely the use of and eventual industry-wide

adoption of Dolby Stereo sound. “Star Wars,” it can be argued, has

influenced the motion picture industry and a generation of moviegoers

more so than any other single motion picture.

Perhaps the lack of coverage in “Empire Of Dreams” is due to the

filmmakers’ desire to avoid addressing the controversy and confusion

that has existed regarding the presentation type audiences experienced

in the opening weeks of release. Numerous books, articles and fan

recollections have attributed “Star Wars” as having an exclusive opening

in the Dolby Stereo process (Dolby System, as it was then known).

Other claims have included “Star Wars” being the first film ever

released in Dolby Stereo, or that all of the initial prints of the film

were in the 70-millimeter wide gauge format. None of the claims

are correct, though by extensively researching the subject it becomes

clear how one could be misled.

Above: 35mm Frame From "Star Wars" With

Optical Soundtrack – Below: 70mm Frame With Magnetic Soundtrack

“Star Wars” was indeed released in Dolby Stereo, but was not the first

film to utilize the then-fledgling technology. A few films prior

to “Star Wars” were released in various forms of Dolby Stereo on a

limited or test engagement basis. Examples include “Tommy” (1975),

“Nashville” (1975), “Lisztomania” (1975), “Logan's Run” (1976), and “A

Star Is Born” (1976). “Star Wars” was the first attempt at a wide

release in the Dolby Stereo format in the sense that all of the prints

put into circulation in the initial wave were Dolby-encoded. All

of the prints, however, were not necessarily decoded during playback

using Dolby equipment; in other words, the initial mono presentations

were Dolby prints played in mono. It appears that the distributor

sought to book “Star Wars,” at the filmmakers’ urging, in as many

theatres as possible willing to install Dolby sound systems. The

number of suitably-equipped venues, however, fell short of the total

number of prints initially put into circulation. As for release

prints in the deluxe (and expensive) 70mm format – with its superior

projection quality and exquisite six-track magnetic audio – they were

kept to a minimum.

But I Swear I Saw ‘Star Wars’ In 70mm

Many technology-savvy and quality-conscious moviegoers may have a

distinct recollection of attending a 70mm (blow-up) presentation of

“Star Wars.” However, in looking over the list of original

engagements some may be surprised to find that only eight 70mm

engagements are noted, and that they were limited to theatres in the Los

Angeles, New York, and San Francisco markets. Ah, but some of you

are positive you saw a 70mm showing at a big, famous theatre in

Washington, D.C., or Dallas, or Chicago, or Detroit, or even Honolulu.

Well, you did... but not during the film's opening weekend!

Throughout the summer and fall of 1977, as “Star Wars” continued to

perform beyond expectations, Fox ordered several new 70mm prints, and

many theatres were provided with a large-format print. By

Christmas 1977,

over two dozen 70mm engagements were playing throughout major cities in

the U.S.

Newspaper ad in Dallas

When people fondly recall the soundtrack experience of “Star Wars” – the

rumble of the Imperial Cruiser in the classic opening scene... the

squeaks and chirps of R2-D2... the hum of the lightsabers... the roar of

the TIE Fighters... the Millennium Falcon's escape from the Mos Eisley

spaceport and jump to hyperspace... the unforgettable John Williams

music score... the climactic explosion of the Death Star... – it is

likely that one's memory is based upon having attended a 70mm Six-Track

Dolby Stereo presentation, with its easily apparent superiority over

conventional 35mm stereo and monaural presentations. While all

things “digital” are commonplace today, back then 70mm was the

Rolls-Royce of the movies.

As a result of the impact of “Star Wars,” the number of theatres

equipped for stereo sound increased significantly, as did the number of

films being mixed for stereo playback. Counting those initial

theatres that installed Dolby for their “Star Wars” engagement, the

number of Dolby-equipped theatres in the world by the end of May 1977

was fewer than 50. By the following year, when the film was

retired from release, the number of equipped venues topped 700. As

for films available with Dolby-encoded soundtracks, the number doubled

in 1978 compared with the previous year and would continue to increase

each year. As well, the 70mm format, which thrived during the

1950s and ’60s, enjoyed a renaissance of sorts with many event movies

being released in the magnetic six-track format on 70mm prints for

selected theatres as well as in optical Dolby on conventional 35mm

prints compatible in all movie theatres throughout the world.

Now You Hear It, Now You Don't

Variations in the soundtrack presentations of “Star Wars” can be traced

to the multiple mixes that were prepared to accommodate the different

formats in which the movie would be released:

1) 35mm stereo (optical, two-track/four-channel)

2) 35mm stereo (magnetic, four-track)

3) 70mm stereo (magnetic, six-track)

4) 35mm mono (optical)

The sound editing and re-recording team began by preparing a four-track

master mix (Left-Center-Right-Surround) which would serve as the basis

for both the 35mm and 70mm stereo versions. First, the master mix

was dubbed to a matrix-encoded two-track Lt-Rt (Left total-Right total)

printmaster for use in creating the 35mm Dolby Stereo prints. Then, the

same four-track master, with some enhancements added, was used to create

the six-track version. In comparison to the 35mm Dolby Stereo

version, the Six-Track Dolby Stereo version during playback offered

discrete channels, greater clarity, superior dynamic range, and two

extra channels for special low-frequency enhancement, in what the Dolby

folks affectionately called “baby boom.” After completing the

multichannel versions, the soundtrack crew created another

English-language mix: a monaural mix. This would be included on

prints destined for theatres not equipped with a stereophonic sound

system and for versions prepared for ancillary markets. The mono

prints were put into circulation upon the wide national break in June

1977.

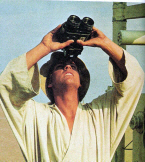

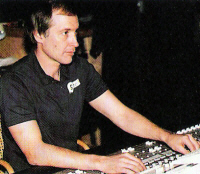

Sound designer Ben Burtt

Although the 35mm Dolby Stereo process is mono-compatible, at the time

those involved with the new technology were, for both technical and

aesthetic reasons, concerned about the effectiveness of mono playback

from a stereo-encoded print. For similar reasons, a decision was

made not to create the mono master by means of dubbing the stereo master

and folding the multiple tracks into one. Instead, a new dedicated

mono mix was created.

With each subsequent mix, the filmmakers seized opportunities to revise

and enhance selected portions of the soundtrack where they had felt

rushed or shortchanged creatively. Sound Designer Ben Burtt

recalls: “Because we were always trying to make the film better and

better and fix things that were not right, there were some sweetener

tracks added; things like different C-3PO or Stormtrooper lines [‘Close

the blast doors’], additional sound effects, or some different ADR [the

dialogue of Aunt Beru].” Knowing that multiple mixes were made

containing subtle yet detectable differences help explain conflicting

memories of moviegoers who remember hearing a certain sound effect or

line of dialogue in one presentation but not in another.

It may be difficult to comprehend today as most major film releases on

DVD sport a 5.1-channel digital soundtrack, but at the time, not knowing

what the future would hold in terms of widespread adoption of

multichannel sound in movie theatres and in homes, some members of the

production felt the mono mix represented the definitive soundtrack of

“Star Wars.” They felt that the stereo version was a novelty that

selected audiences would be treated to only during a brief theatrical

run. “George put a lot of effort in that mono mix,” Burtt

remembers. “And he even said several times, ‘Well, this is the

real mix. This is the definitive mix of the film.’ He paid

more attention to it because he felt it was more important archivally.”

Conclusion

No matter how often George Lucas waves his magic wand and makes changes

to “Star Wars,” for many, the memory of experiencing the magical

space-fantasy in 1977 will never fade. Perhaps this explains the

enduring appeal of the movie, despite the ongoing revisions made to it.

This article was written to preserve those memories and to provide a

history of the original release of the movie. Obi-Wan Kenobi was

right: The Force will be with [us]...always.